Someone somewhere on Substack said recently that in order to combat our self-doubt and lack of productivity, we could write short essays instead of the thorough, lengthy pieces that we might feel are what we ought to be publishing here. I agreed enthusiastically and then didn’t take the advice.

I hope to turn my own personal tide here!

I keep thinking I’d like to publish more here, but then I am overwhelmed by the thought of the time and effort it takes to write something that doesn’t meet my standards. This is in part because I read so many great publications here. But this is also because “I don’t have time” is such a familiar voice in my head. I use that sentence to put an end to lots of things I actually want to do, in favor of the things I have to do. I don’t actually have to write anything on substack. I just want to.

But there is a long-term benefit to writing, which is that the more you do it, the better you get. Taking a moment to consider this, it’s true of many things. And getting better actually crosses over to the have to column. I don’t plan to leave this earth without getting better at a number of things, and writing is one of them. I intend to get better at both quality and quantity. I’m too slow at writing and I know it gets in the way of the writing itself because then I never finish things and put them out.

I learn a lot from Bunsuke, who has a Ph.D. in Japanese literature and publishes a super helpful Substack newsletter with snippets from Japanese literature, vocabulary lists, and a translation. You can use them to test your ability or even use it as a regular study tool. He teaches both group and private lessons, but he also puts out a lot of helpful advice free on his youtube channel.

I read a lot of Japanese material, and the “I don’t have time” voice is usually somewhere in my head, so when I see things I can’t read or annoyingly long sentences where I can’t exactly tell who is doing what to whom, I often skip them. This isn’t completely useless—you do get better just by continuing to expose yourself to the literary language. So I haven’t given up completely, but sometimes I feel frustrated that I have spent so many years with this language (and grew up surrounded by it) and I still feel so inept.

The second thought that tries to defend my behavior is always, “reading the actual source material in Japanese is optional.” Except reading in the language is simply not the same as reading a translation. So the “optional” excuse is kind of a fib, isn’t it. If I want to truly get into the material, I have to read it in Japanese. Otherwise I have an intermediary, which is fine for many purposes, but it doesn’t work for my particular path.

This is true in spades for my current research project, where there just isn’t a lot of English-language material. If I want to do a competent job, I can’t avoid reading these texts in Japanese. And when I go to Japan, I don’t have a choice. The signs and monuments for the historic sites I am interested in are not always translated.

I asked Bunsuke this question recently: should I really be looking up every single character? (My mind responds: I don’t have time!)

And his answer was: pick an amount of time that you can manage, and for that amount of time, look everything up. Then stop. And for the rest of the day, you can just read casually and skip things you don’t know. But do the hard work every day, for that small amount of time.

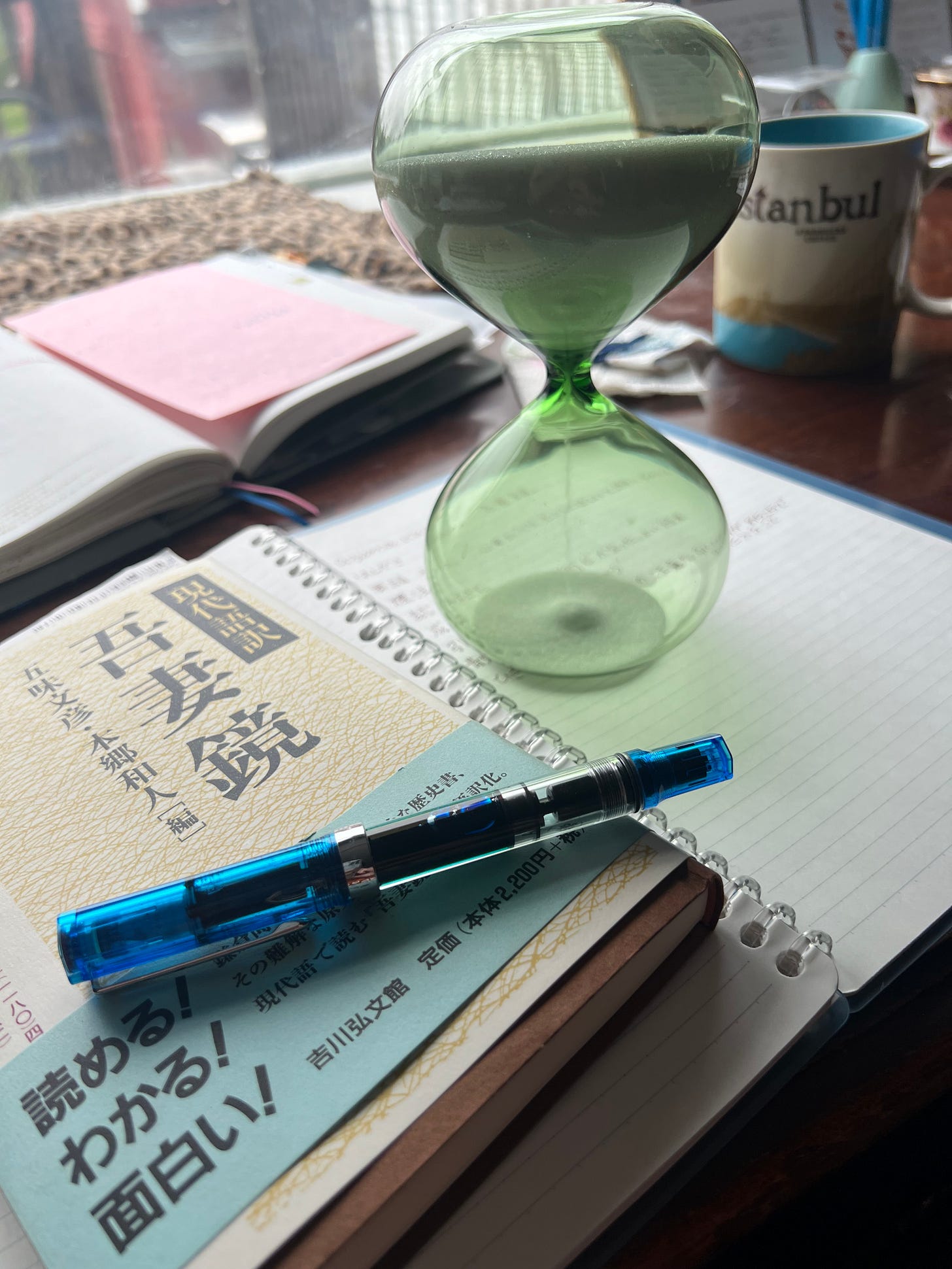

I’m doing it. And it’s hard. It’s frustrating. And the voices are still in my head! But I have to agree that it improves your recall, especially if you thumb through actual print materials in order to locate the right character or definition. It has forced me to pick up a pen and actually write in Japanese when I take notes. And it really isn’t that painful. Okay, it is that painful, but the pain only lasts for as long as it takes for the sand to run out in my hourglass. It’s like programming the elliptical for a quick fifteen-minute workout and knowing that when you’re done, you’ve punched the card and can go about your day.

I hope I can put in a similar effort with my writing here. I’d like to write more and publish more; that means shorter pieces that aren’t very tight or focused. I know I need to put in the work. (And I just realized that I’ve written a lot more than I thought I would!)

I especially like one of Bunsuke’s recent videos listing tips on how to start reading literature in Japanese:

Right now I’m only managing 2-3 pages at each sitting where I look everything up. I hope I do better as I go along.

You think and feel so deeply - and it’s obvious how much your writing & Japanese mean to you.

Thank you so much for sharing. Taking the time that you have to do what you can do is AMAZING. ✨

Thanks for taking us with you on your language journey, Maya.

I have studied four foreign languages and handle three fairly well — one of which is English. I also taught English and ran a chain of language schools at the start of my career in the 1980s and 1990s.

One trick that I have used as a learner, and taught as a teacher and school director, was to not look up every single word you don’t know.

Try to infer the meaning from context. It is no problem if you get some wrong at first — eventually you get it right.

If you regularly encounter the same word and still can’t figure out the meaning with some level of confidence, go and look up that darn rebel.

It is also OK to look up the words that you can’t guess at all, but which are clearly key to the meaning of the passage.

This strategy effectively limits you to looking only up the words with high frequency, and the words that are key to understanding the passage at hand. You won’t waste your time on words that you may never, or rarely, encounter again, or that at this point in your study don’t really make much of a difference to your understanding and fluency.

It means accepting a level of vagueness at the start of the journey that you would probably not accept in your native language, but I have found that it lowers the frustration quite a bit, while simultaneously speeding up the learning process.